Name: Ayana Bhattacharya , UG-2, Roll No.- 07.

“Under your skin the moon is alive.”-Pablo Neruda

Such is the ethereal beauty of Venus, with which she has baffled gods and mortals over the ages, inspiring men to write and paint to capture her true essence. In classical Rome, she was worshipped as the goddess of love, sex, beauty, fertility, and was the counterpart to the Greek Aphrodite. Long after the decline of the Roman Empire she has continued to influence Western Art and Literature, with each age discovering her in a new light. Roman and Hellenistic art produced many beautiful sculptures of nude women which in modern art history are referred to as Venuses. Most famous among this kind of sculptures which have been discovered is the marble statue Venus de Milo, created sometime between 130-100 BCE. Another well-known Pompeian mural named Venus Anadyomene depicts Aphrodite on a scallop shell in the sea from which she was born. By early medieval times, with the triumph of Christianity she was seen as the incarnation of sinful lust and depravity. However in the Renaissance, she was celebrated for her beauty and sexuality and explorations in love. Painters returned to Venus time and again to capture her persona through various mythologies, imbued with their understanding of the pagan goddess and artistic mastery.

Being the goddess of sexuality, Venus has mostly been depicted as a nude woman in Western Art. The Greeks celebrated nudity, especially in males (Gods and athletes) and later in females, in an unparalleled way. In the mid-fourth century, the sculptor Praxiteles made a nude Aphrodite called the Knidian, which probably established a new trend of female nudes in Greek sculpture, having idealized proportions based on mathematical ratios as was the male nudes. However this view of nudity is much opposed to the Biblical connotations of shame and sin associated with nakedness. Hence in the Christian Middle Ages, celebrating chastity and celibacy, nudity was allowed only in certain religious contexts, both in western and byzantine art. The rediscovery of classical culture in the Renaissance restored the nude to art. The first male nude of the Renaissance, a young bronze David, had been modeled from life in 1430 by Florentine sculptor Donatello. The monumental female nude returned to Western art in 1486 with The Birth of Venus, by Sandro Botticelli for the Medici family, who also owned the classical Venus de’ Medici, whose pose Botticelli adapted. Various other Renaissance artists have attempted at crystallizing different moods of the goddess modeling her on beautiful women.

THE BIRTH OF VENUS- BOTTICELLI

PRIMAVERA- BOTTICELLI

In Botticelli’s famous 1486 painting we behold a nude Venus, rising from the sea with all grace and beauty. This painting alludes to Venus’s birth as is evident from the title. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Aphrodite was born of the foam from the sea produced after Saturn (Greek Cronus) castrated his father Uranus (Ouranus) and his blood fell to the sea. The Birth of Venus depicts the moment when, having emerged from the sea in a shell, Venus lands at Paphos in Cyprus. She is being blown towards the shore by Zephyrus – god of the winds – and the breeze Aura, while a Hora of Spring stands on dry land poised to wrap a cloak, decorated with spring flowers, around Venus to cover her nudity. The goddess, at the moment of her birth stands on the clam shell in the form of a full grown woman. She has a calm and distant look in her eyes, as if unaffected by the drama of her creation. Unlike the narrow chested slight figures with gentle curves and a bulged stomach of the gothic female nude, Botticelli’s Venus stands on the shell in the classical contrapposto position, resting her weight on one leg with a chaste gesture. The land towards which she is approaching has both laurel and myrtle growing on it and roses (the symbol of Venus) are raining from the skies. The richness of the painting is borne out by the depiction of motion mostly noticeable in the flying drapes of Zephyrus and the Hora, the falling roses and the goddess’s beautiful hair ruffled by the wind. The theme of love triumphs over brutality is reflected in this painting of Venus as the goddess of Love springs from a brutal action of a son against a father. She has been painted as having a pearly white skin and blonde hair as was the fashion during the Renaissance. She appears to be shielding her sexuality in a chaste manner by covering her bare breasts and naked vulva with her hands and flowing red hair. Though Venus’s naked beauty has been attractively revealed, the sensual aspect to it has been surpassed by a divine essence. The initial physical response of the viewer gives way to an elevated feeling of a love and grace beyond the limits of the body while looking at her figure in this painting. This is the ideal depiction of Venus as a goddess as she floats on the foaming sea. Her portrayal in another painting by Botticelli, La Primavera, is again desexualized and this time she appears clothed. This tempera, also known as the Allegory Of Spring, shows a Humanistic flavor, and here love takes a central position. The setting is that of a forested area, rich with fruits and flowers, signifying the coming of spring. the painting shows nine figures- the three Graces dancing in their Botticelli-an flowing garments representing the feminine virtues of Chastity, Beauty, Love, Mercury ushering away the winter clouds with his staff, Cupid with his bow and arrow, and Zephyr forcing himself on Chloris and her transformation into Flora, and in the center stands a clothed Venus representing philanthropy. Love, marriage and resultant sexual union seems to be the essential vein of the Primavera, as symbolized by a divine Venus. Here Venus embodies love in her divine form.

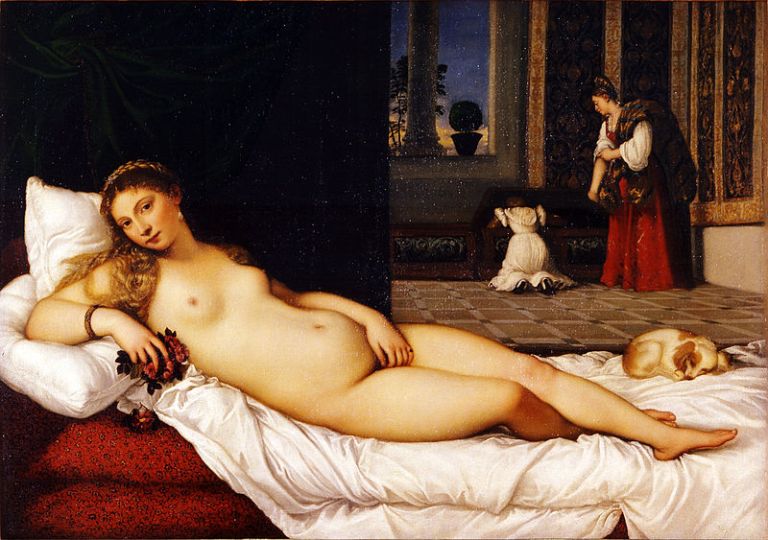

VENUS OF URBINO- TITIAN

THE SLEEPING VENUS- GIORGIONE

VENUS WITH A MIRROR- TITIAN

In Titan’s painting Venus of Urbino, the “donna nuda” is all bold and beautiful. There has been much conjecture on the identity of this naked woman, diversely concluding her to be the Duke Guidobaldo of Urbino’s mistress, or Titian’s own mistress, or more daringly Eleonora Gonzaga, the beautiful and intelligent mother of the current Duke. The figure has been identified with Venus because of the suggestive symbols of the Greek goddess, like the bunch of roses she playfully holds and the myrtle in the background viewed through the window in the room. The nudity of the reclining Venus is emphasized by showing fully-clothed servant women in the background. The reclining Venus was originally devised by Venetian Giorgione in his painting, the Sleeping Venus or the Dresden Venus, in 1510. This painting was completed by Titian (he finished the landscape and the sky) after Giorgione’s death. The figure in this painting has “the aura of a nature goddess” (Rosie-Marie and Rainer Hagen). Though her hand on her groin has erotic implications, the peaceful expression on her face distils the sensuality of her nudity, as if immersed in the recollection of love in her dreams. To quote Sydney Freedberg, “(she is) the perfect embodiment of Giorgione’s dream, she dreams his dream herself”. More than a quarter of a century later, when Titan returns to the same theme, he places his Venus in a man-made setting unlike the natural setting of his senior colleague. Titan’s Venus, liberated from the mythical stereotypes, assumes the figure of a mortal female rather than a goddess. Instead of peacefully slumbering, this figure boldly meets the spectators’ gaze, revealing her blooming sensuality and beauty. In this painting the dark background of the supposed curtain of the bed, in a way separates the reclining woman from the reality of the rich life. The vertical border of this dark plane also emphasizes her act of coyly covering her pubic region. Her urging sexuality, engages the spectator in a dream of reality rather than awakening a sense of loftiness linked to divinity. In Venus with a Mirror, Titian paints a voluptuous figure (unlike the sleek figure in the in the Sleeping Venus) classical pose of “Venus Pudica” or the modest Venus. However her modesty is somewhat compromised by the obvious pleasure she takes in her own beauty as reflected by the mirror. This was one of the most popular subjects to be treated by the artist and there exist some 15 copies and variants painted by the master himself or his assistants. The painting shown here was probably the first copy, but this fact is open to debate. Here the artist fleshes out his imagination of the goddess in a narcissistic mood. Two Cupids or Amorini can be seen attending Venus, one holding up the mirror for her, while the other reaches out to place a crown on her head. The most interesting thing about this painting is how it captures the politics of sight. The intriguing question is that what is the goddess really looking at? Is it herself, or is she stealing a glimpse of the unaware spectator outside the frame, immersed in awe of her? Here, with his master brushstrokes the artist creates the “Venus effect” i.e. a psychological effect which states that since the eyes of Venus are reflected in the mirror itself (as in many paintings of Venus with a mirror), she is actually looking at the viewer or painter outside the canvas. So, perhaps Titian was imagining himself as the lover envious of the mirror who could enjoy the mistress’s beauty so easily, just like in the words of poet Serafino dall’Aquila-

“Oh, mirror, I envy you only because of her…Alas! I would like to trade my place with yours…”

Another noticeable fact is that the artist shows Cupid, the god and perpetrator of erotic love and desire, holding the mirror perhaps to project Venus’s reflection as an erotic manifestation of love as opposed to a kind of pure love that the goddess’s divinity would connote.

VENUS AND ADONIS- TITIAN

So far in the paintings we have looked at, it is Venus who either has the agency over the spectator (as in Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Venus with a Mirror) being the central figure, or has a distant look about her which elevates her to a state of divinity in which no one has power over her (as seen in both Primavera and The Birth of Venus by Botticelli). However when other figures like her lovers Adonis and Mars and her husband Vulcan enters the canvas space, she is seen through a kaleidoscope of mythologies where she is in interaction with the other characters and ceases to be the central figure of agency. Such a scenario is observed in Titian’s Venus and Adonis, which is the artist’s rendering of the Ovidian myth of the Greek goddess and her young mortal lover. There are various versions of this painting, but here we will be referring to the one painted by the artist in 1554. In Ovid’s tale Venus, accidentally wounded by one of her son Cupid’s arrows, falls in love with the handsome hunter Adonis and, forgetting her divine duties, descends to earth to spend time with him. To please her young lover the goddess takes up hunting and pursues harmless prey, warning Adonis about the perils that can befall the hunter. When the goddess returns to her realm Adonis, careless of her warning, is slain by a wild boar. When he dies, Venus turns the blood drops that fell from his wounds onto the soil into windflowers (the short-lived anemone) as a memorial to their love. Titian chooses to depict the emotionally charged valedictory moment of the lovers when Venus tries to resist Adonis from going to the hunt. Interestingly the goddess here has been presented as a victim of love in opposition to her normal role as the object of love. She is no more a dignified, indifferent representation of the divine feminine ideal but becomes a frantic woman who is trying to exert every possible power and strength within to inhibit the man she loves from abandoning her and thus succumbing to his death, in the hands of the artist. She is desperate in her attempts and physically restrains Adonis from embarking on a journey towards his doom. With his soft, luxuriant strokes, Titian succeeds in freezing the anxiety and spontaneity of the moment in time. The composition’s dynamism springs from the torsion caused by Venus’s awkward pose, which was inspired by an ancient sculptural relief. The artist had probably painted Venus from behind so as to capture her beauty in entirety, but this somehow makes her look the more vulnerable figure of the two. While Adonis looks down at her with an impassive look, Cupid is asleep in the background with his arrows uselessly hanging on a tree, signifying the ineffectiveness of the goddess’s earnest plea to her lover. Adonis’s hunting dogs seems to be straining at their leashes, reflecting the urgency and impatience of the man himself. The poignancy and raw emotion of the moment harkens back to Ovid’s account of the imminent death of the lover and Venus’s intense grief – “(She) leaped downe, and tare at once hir garments from her brist,/ And rent her heare, and beate upon her stomack with her fist.”

MARS AND VENUS- BOTTICELLI

PARNASSUS- MANTEGNA

MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN- TINTORETTO

Another lover of Venus, Mars, the god of war, shares the frame with her in many Renaissance paintings. In Botticelli’s, Mars and Venus, once again it is Venus who has agency over an unarmed figure of Mars. The painting seems to be that of a post-coital moment. In contrast to Mars’s practically naked and somnolent state, the goddess is fully clothed, awake and alert. Mars is sleeping the ‘little death’ which comes after making love, and not even a trumpet in his ear will wake him. The little satyrs have stolen his lance – a joke, to show that he is now disarmed in love. One satyr carries off his helmet and the other one rests inside Mars’s breastplate. The wasps encircling his head are probably a reference to the symbol of the Vespucci family who might have commissioned this painting. Alternatively they could also represent the stings of love. On a psychological plane, Venus, symbolizing love, has succeeded in disarming Mars, the symbol of war; her victory over him is complete as evident from the complacent look in her face. As she seems to be surveying her worn-out lover, she looks on him with little emotion and more satisfaction of having complete power over him. Thus in this Botticelli painting we observe a translation of the Humanist idea of love conquering war into art. Venus’s expression also seems to befit that of a goddess who is always in agency, an inevitable condition of her divinity. In Mantegna’s Parnassus or Mars and Venus Venus celebrates celestial love at the center of the Greek world, on Mount Parnassus, the site of the Delphic Oracle. With his soft strokes, the artist fleshes out a nude Venus beside an adoring figure of Mars clad in his armor. The goddess’s nudity transcends erotic implications to indicate a sublime purity like that of Eve in the prelapsarian state. The two gods are shown on a natural arch of rocks in front a symbolic bed; in the background the vegetation has many fruits in the right part (the male one) and only one in the left (female) part, symbolizing the fecundation. This reveals that the love being celebrated is not just Platonic but has a procreative aspect to it. The painting is populated by many mythical figures presenting an interesting coalescence. This painting was commissioned by Isabella d’Este for her studiolo (studioli were reserves of Humanist culture and the vogue of 15th century Italian court). The reflection of a Humanist spirit can be found in Parnassus which depicts the nine muses, the goddesses of inspiration of literature, science, and the arts, dancing beneath the two lovers as a symbol of universal harmony while Apollo plays a lyre. Mercury resides on the far right, alongside Pegasus, the allegory for fame and moral achievement. The presence of Vulcan, Venus’s husband however challenges the positive and celestial image of Venus. There seems to be an implicit suggestion of moral transgression on the part of the goddess against which Vulcan ineffectively rebels from the dark corner of his workshop in a grotto that the artist assigns him. His mere presence implicates that the union of Mars and Venus is an illicit affair, providing a negative connotation on Venus’s behalf. The ingenious portrayal of Anteros aiming a blowpipe towards a cursing Vulcan is perhaps a representation of the fact his love for Venus is unrequited. Though the painting seems to celebrate a requited celestial love between two gods, the illegitimacy of it has been again emphasized by Mantegna by painting both Venus and Vulcan nude, subtly indicating a shared bond of legitimacy between them. Thus we see that Venus, in Mantegna’s imagination, is caught between a discourse of legitimacy and promiscuity, though she seems to be completely unaware of the uncertainty of her position. This discourse gets further magnified in Jacopo Tintoretto’s Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, a mannerist painting instilled with piquant humor. The painting refers to the Greek myth in which Vulcan (Hephaestus) had cast a fine almost invisible net to ensnare his wife Venus (Aphrodite) and her lover Mars together. Tintoretto chooses to capture the highly melodramatic moment where the lame god discovers his wife with her lover and adds a subtle twist to the story. In the painting, Vulcan seems completely unaware of or uninterested in Mars hiding beneath a table or the lap dog barking at him. He has one knee on the bed on which Venus is stretched out alone and appears to be lifting the piece of cloth covering Venus’s groin. In this action, he seems more distracted by the nudity of his beautiful wife than actually trying to find proof of Venus and Mars’s sexual encounter between her thighs. This comical representation of Vulcan is probably further emphasized by the optical illusion created by the reflection on the round mirror (or shield) across the room which shows Vulcan bending over the naked body of his wife. The mirror, as if acting like an omniscient eye, focuses only on the divine cuckold who at this moment seems oblivious of his actual purpose of trying to expose the transgressive lovers. Venus on the other hand, alluring in her naked sensuality, does not betray any emotion of guilt. Though she tries to cover herself with a cloth in a futile attempt, her face interestingly does not show any sign of shame or anxiety. The artist depicts a cupid asleep in a cot in a corner, not participating in the adrenaline rush around him. Perhaps Tintoretto had tried to show Venus’s reaction as one of nonchalance to the scene around her as she knows that in spite of being blasphemed for her affairs outside her marriage, she would not confine her expression of love to any one person.

VENUS, CUPID, FOLLY AND TIME- BRONZINO

The figure of Venus becomes the ultimate representation of eroticism and ambivalence characteristic of Mannerist art in Agnolo Bronzino’s painting Mannerism is a style of painting which developed in Italy during the 1520s and exaggerated and distorted the defining characteristics of High Renaissance art, creating unsettling, sometimes bizarre pictures. Bronzino was commissioned this painting around 1546 probably by Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany or by Francesco Salviati, to be presented by him as a gift to Francis I of France. The erotic imagery would have appealed to the tastes prevalent in both the Medici and French courts at this time. At the center of the painting is a naked, adolescent Cupid holding Venus, his mother, in close embrace, kissing her lips and fondling her breast. To their right is a nude putto who has been interpreted as Folly. The laughing boy is showering the couple with rose petals (rose being an attribute of Venus). Behind him is the grotesque figure with the head of a girl, scaly serpentine body and legs of a lion, holding a honeycomb in her hand has been called Pleasure. This ridiculous compilation of many body parts in the body of Pleasure probably shows her various facets. The old man Time, as identified by the hourglass beside him, imposingly appears on the top of the canvass. With his strong hands he grasps a brilliant blue drapery while trying to prevent the figure on the extreme left (Oblivion) from veiling the transgressive lovers from sight. This resolute action by Time seems to suggest that he want the world to remember this incestuous pairing and not push this scene into oblivion. Many scholars believe that his gesture seems to say “Time is fleeting, and you never know when it may be all over.” The figure at extreme left has probably been called Oblivion because of the lack of his form and substance, his face appearing almost mask-like. The old lady raving and tearing her hair behind Cupid had been identified as Jealousy, though some scholars believe her to represent the ravaging effects of syphilis resulting from unwise sexual intercourse. From such a populated background with figures jostling for space, the theme of the painting, i.e. lust, deceit and jealousy, becomes clear. Cupid, Venus and folly are all posed in the typical Mannerist form. The nude figure of Venus here becomes not only sexual but also incestuous. She, besides holding the golden apple which she got in the Judgement of Paris, grasps Cupid’s bow, implying that she is the one in control in this sexual tryst. She seems to be slippin g her tongue into Cupid’s mouth, which is perhaps the most blasphemous aspect of the painting. Thus, here she transcends the role of a mother to Cupid and becomes the ultimate representation of femininity, young, beautiful and desirable.

This beautiful soul, Venus, whose essence man can never have enough, unravels a world of mystery before us. At times she is remote, while at others one can feel the soft touch of her pearly white skin against one’s own as she transcends her divinity through her sexuality. She seems to be a creature beyond human grasp, eluding our sense of wonder, engaging us in an eternal chase to contain her, to define what she really is. The flame of love rages in her being, burning to ash every impurity of this mundane world. Through her, sexuality transforms into something beyond the mere physicality of flesh and blood. Her quiet, somber expression,and beautiful sad eyes, as captured in Botticelli’s canvas, perhaps reveals the truth about the one who can never die, because she is the goddess of the force that turns the world around- Love.

BIBLIOGRAPHY-

- Marie, Rose and Rainer Hagen. What Great Paintings Say- From Bayeux Tapestry to Diego Rivera- Volume 1. Koln: Taschen, 2003.

- Manca, Joseph.Andrea Mantegna and the Italian Renaissance. New York: Parkstone International, 2012.

- Williams, Jay. The World Of Titian. New York: Time- Life Books, 1968.

- “Venus with a Mirror”. Accessed November 19, 2015. http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/highlights/highlight41.html

- “Tintoretto”. The Art Tribune. Accessed November 19, 2015.

Hi, Cool post. I am looking forward to read more of your work.

LikeLike